[9][10][n 1] The original M16 was a select-fire,5.56×45mm rifle with a 20-round magazine.

In 1964, the M16 entered American military service and the following year was deployed for jungle warfare operations during the Vietnam War.[1] In 1969, the M16A1 replaced theM14 rifle to become the U.S. military’s standard service rifle.[13][14] The M16A1 improvements include a bolt-assist, chrome plated bore and a new 30-round magazine.[1] In 1983, the USMC adopted the M16A2 rifle and the U.S. Army adopted it in 1986. The M16A2 fires the improved 5.56×45mm NATO (M855/SS109) cartridge and has a new adjustable rear sight, case deflector, heavy barrel, improved handguard, pistol grip and buttstock, as well as a semi-auto and three-round burst only fire selector.[15][16] Adopted in 1998, the M16A4 is the fourth generation of the M16 series.[17] It is equipped with a removable carrying handle and Picatinny rail for mounting optics and other ancillary devices.[17]

The M16 has also been widely adopted by other militaries around the world. Total worldwide production of M16s has been approximately 8 million, making it the most-produced firearm of its 5.56 mm caliber.[18] The U.S. Army has largely replaced the M16 in combat units with the shorter and lighter M4 carbine,[19] and the U.S. Marine Corps approved a similar change in October 2015.[20]

Background

After World War II, the United States military started looking for a single automatic rifle to replace the M1 Garand, M1/M2 Carbines, M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle, M3 “Grease Gun” and Thompson submachine gun.[21][22] However, early experiments with select-fire versions of the M1 Garand proved disappointing.[23] During the Korean War, the select-fire M2 carbine largely replaced the submachine gun in US service[24] and became the most widely used Carbine variant.[25] However, combat experience suggested that the .30 Carbine round was under-powered.[26] American weapons designers concluded that an intermediate round was necessary, and recommended a small-caliber, high-velocity cartridge.[27]

However, senior American commanders having faced fanatical enemies and experienced major logistical problems during WWII and the Korean War,[28][29][30][31][32] insisted that a single powerful .30 caliber cartridge be developed, that could not only be used by the new automatic rifle, but by the new general-purpose machine gun (GPMG) in concurrent development.[33][34] This culminated in the development of the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge and the M14 rifle[33] which was an improved M1 Garand with a 20-round magazine and automatic fire capability.[35][36][37] The US also adopted the M60 general purpose machine gun (GPMG).[33] Its NATO partners adopted the FN FAL and HK G3 rifles, as well as the FN MAG and Rheinmetall MG3 GPMGs.

The first confrontations between the AK-47 and the M14 came in the early part of the Vietnam War. Battlefield reports indicated that the M14 was uncontrollable in full-auto and that soldiers could not carry enough ammo to maintain fire superiority over the AK-47.[35][38] And, while the M2 carbine offered a high rate of fire, it was under-powered and ultimately outclassed by the AK-47.[39] A replacement was needed: a medium between the traditional preference for high-powered rifles such as the M14, and the lightweight firepower of the M2 Carbine.

As a result, the Army was forced to reconsider a 1957 request by General Willard G. Wyman, commander of the U.S. Continental Army Command (CONARC) to develop a .223 caliber (5.56 mm) select-fire rifle weighing 6 lb (2.7 kg) when loaded with a 20-round magazine.[21] The 5.56 mm round had to penetrate a standard U.S. helmet at 500 yards (460 meters) and retain a velocity in excess of the speed of sound, while matching or exceeding the wounding ability of the .30 Carbine cartridge.[40]

This request ultimately resulted in the development of a scaled-down version of the Armalite AR-10, called AR-15 rifle.[8][9][41] However, despite overwhelming evidence that the AR-15 could bring more firepower to bear than the M14, the Army opposed the adoption of the new rifle.[8][35] In January 1963, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara concluded that the AR-15 was the superior weapon system and ordered a halt to M14 production.[8][35] At the time, the AR-15 was the only rifle available that could fulfill the requirement of a universal infantry weapon for issue to all services.

After modifications (most notably, the charging handle was re-located from under the carrying handle like AR-10 to the rear of the receiver),[9] the new redesigned rifle was subsequently adopted as the M16 Rifle and went into production in March 1964.[1][8] “(The M16) was much lighter compared to the M14 it replaced, ultimately allowing soldiers to carry more ammunition. The air-cooled, gas-operated, magazine-fed assault rifle was made of steel, aluminum alloy and composite plastics, truly cutting-edge for the time. Designed with full and semi-automatic capabilities, the weapon initially did not respond well to wet and dirty conditions, sometimes even jamming in combat. After a few minor modifications, the weapon gained in popularity among troops on the battlefield.”[35][42][43]

Adoption

In July 1960, General Curtis LeMay was impressed by a demonstration of the ArmaLite AR-15. In the summer of 1961, General LeMay was promoted to United States Air Force, Chief of Staff, and requested 80,000 AR-15s. However, General Maxwell D. Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, advised President John F. Kennedy that having two different calibers within the military system at the same time would be problematic and the request was rejected.[44] In October 1961, William Godel, a senior man at the Advanced Research Projects Agency, sent 10 AR-15s to South Vietnam. The reception was enthusiastic, and in 1962, another 1,000 AR-15s were sent.[45] United States Army Special Forces personnel filed battlefield reports lavishly praising the AR-15 and the stopping-power of the 5.56 mm cartridge, and pressed for its adoption.[35]

The damage caused by the 5.56 mm bullet was originally believed to be caused by “tumbling” due to the slow 1 in 14-inch (360 mm) rifling twist rate.[35][44] However, any pointed lead core bullet will “tumble” after penetration in flesh, because the center of gravity is towards the rear of the bullet. The large wounds observed by soldiers in Vietnam were actually caused by bullet fragmentation, which was created by a combination of the bullet’s velocity and construction.[46] These wounds were so devastating, that the photographs remained classified into the 1980s.[47]

U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara now had two conflicting views: the ARPA report[48] favoring the AR-15 and the Army’s position favoring the M14.[35] Even President Kennedy expressed concern, so McNamara ordered Secretary of the Army Cyrus Vance to test the M14, the AR-15 and the AK-47. The Army reported that only the M14 was suitable for service, but Vance wondered about the impartiality of those conducting the tests. He ordered the Army Inspector General to investigate the testing methods used; the Inspector General confirmed that the testers were biased towards the M14.

In January 1963, Secretary McNamara received reports that M14 production was insufficient to meet the needs of the armed forces and ordered a halt to M14 production.[35] At the time, the AR-15 was the only rifle that could fulfill a requirement of a “universal” infantry weapon for issue to all services. McNamara ordered its adoption, despite receiving reports of several deficiencies, most notably the lack of a chrome-plated chamber.[49]

After modifications (most notably, the charging handle was re-located from under the carrying handle like AR-10 to the rear of the receiver),[9] the new redesigned rifle was renamed the Rifle, Caliber 5.56 mm, M16.[1]</ref>[8] Inexplicably, the modification to the new M16 did not include a chrome-plated barrel. Meanwhile, the Army relented and recommended the adoption of the M16 for jungle warfare operations. However, the Army insisted on the inclusion of a forward assist to help push the bolt into battery in the event that a cartridge failed to seat into the chamber. The Air Force, Colt and Eugene Stoner believed that the addition of a forward assist was an unjustified expense. As a result, the design was split into two variants: the Air Force’s M16 without the forward assist, and the XM16E1 with the forward assist for the other service branches.

In November 1963, McNamara approved the U.S. Army’s order of 85,000 XM16E1s;[35][50] and to appease General LeMay, the Air Force was granted an order for another 19,000 M16s.[51][52] In March 1964, the M16 rifle went into production and the Army accepted delivery of the first batch of 2,129 rifles later that year, and an additional 57,240 rifles the following year.[1]

n 1964, the Army was informed that DuPont could not mass-produce the IMR 4475 stick powder to the specifications demanded by the M16. Therefore, Olin Mathieson Company provided a high-performance ball propellant. While the Olin WC 846 powder achieved the desired 3,300 ft (1,000 m) per second muzzle velocity, it produced much more fouling, that quickly jammed the M16s action (unless the rifle was cleaned well and often).

In March 1965, the Army began to issue the XM16E1 to infantry units. However, the rifle was initially delivered without adequate cleaning kits[35] or instructions because Colt had claimed the M16 was self-cleaning. As a result, reports of stoppages in combat began to surface.[35] The most severe problem, was known as “failure to extract”—the spent cartridge case remained lodged in the chamber after the rifle was fired.[35][53] Documented accounts of dead U.S. troops found next to disassembled rifles eventually led to a Congressional investigation.[35][54]

We left with 72 men in our platoon and came back with 19, Believe it or not, you know what killed most of us? Our own rifle. Practically every one of our dead was found with his (M16) torn down next to him where he had been trying to fix it.

— Marine Corps Rifleman, Vietnam.[54][55]

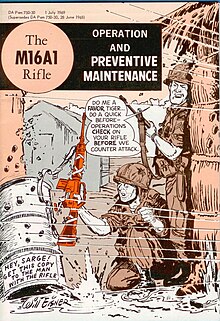

In February 1967, the improved XM16E1 was standardized as the M16A1.[51] The new rifle had a chrome-plated chamber and bore to eliminate corrosion and stuck cartridges and other, minor, modifications.[35] New cleaning kits, powder solvents and lubricants were also issued. Intensive training programs in weapons cleaning were instituted including a comic book-style operations manual.[56][57] As a result, reliability problems diminished and the M16A1 rifle achieved widespread acceptance by U.S. troops in Vietnam.[35][43]

In 1969, the M16A1 officially replaced the M14 rifle to become the U.S. military’s standard service rifle.[13][14] In 1970, the new WC 844 powder was introduced to reduce fouling.[58]

Reliability

During the early part of its career, the M16 had a reputation for poor reliability and a malfunction rate of two per 1000 rounds fired.[59] The M16’s action works by passing high pressure propellant gasses tapped from the barrel down a tube and into the carrier group within the upper receiver, and is commonly referred to as a “direct impingement gas system”. The gas expands within a donut shaped gas cylinder within the carrier. Because the bolt is prevented from moving forward by the barrel, the carrier is driven to the rear by the expanding gasses and thus converts the energy of the gas to movement of the rifle’s parts. The bolt bears a piston head and the cavity in the bolt carrier is the piston sleeve. It is more correct to call it an “internal piston” system.”[60] This design is much lighter and more compact than a gas-piston design. However, this design requires that combustion byproducts from the discharged cartridge be blown into the receiver as well. This accumulating carbon and vaporized metal build-up within the receiver and bolt-carrier negatively affects reliability and necessitates more intensive maintenance on the part of the individual soldier. The channeling of gasses into the bolt carrier during operation increases the amount of heat that is deposited in the receiver while firing the M16 and causes essential lubricant to be “burned off”. This requires frequent and generous applications of appropriate lubricant.[21] Lack of proper lubrication is the most common source of weapon stoppages or jams.[21]

The original M16 fared poorly in the jungles of Vietnam and was infamous for reliability problems in the harsh environment. As a result, it became the target of a Congressional investigation.[61] The investigation found that:[1]

- The M16 was billed as self-cleaning (when no weapon is or ever has been).

- The M16 was issued to troops without cleaning kits or instruction on how to clean the rifle.

- The M16 and 5.56×45mm cartridge was tested and approved with the use of a DuPont IMR8208M stick powder, that was switched to Olin Mathieson WC846 ball powder which produced much more fouling, that quickly jammed the action of the M16 (unless the gun was cleaned well and often).

- The M16 lacked a forward assist (rendering the rifle inoperable when it jammed).

- The M16 lacked a chrome-plated chamber, which allowed corrosion problems and contributed to case extraction failures. (This was considered the most severe problem and required extreme measures to clear, such as inserting the cleaning-rod down the barrel and knocking the spent cartridge out.)

101st Airborne trooper carrying an M16A1 during the Vietnam War (circa 1969). Note: 20-round magazine.

When these issues were addressed and corrected by the M16A1, the reliability problems decreased greatly.[51] According to a 1968 Department of Army report, the M16A1 rifle achieved widespread acceptance by U.S. troops in Vietnam.[43] “Most men armed with the M16 in Vietnam rated this rifle’s performance high, however, many men entertained some misgivings about the M16’s reliability. When asked what weapon they preferred to carry in combat, 85 percent indicated that they wanted either the M16 or its [smaller] submachine gun version, the XM177E2.” Also “the M14 was preferred by 15 percent, while less than one percent wished to carry either the Stoner rifle, the AK-47, the carbine or a pistol.”[43] In March 1970, the “President’s Blue Ribbon Defense Panel” concluded that the issuance of the M16 saved the lives of 20,000 U.S. servicemen during the Vietnam War, who would have otherwise died had the M14 remained in service.[62] However, the M16 rifle’s reputation continues to suffer.[51][63]Currently, the M16 is in use by 15 NATO countries and more than 80 countries worldwide.

Design

The M16 is a lightweight, 5.56 mm, air-cooled, gas-operated, magazine-fed assault rifle, with a rotating bolt. The M16’s receivers are made of 7075 aluminum alloy, its barrel, bolt, and bolt carrier of steel, and its handguards, pistol grip, and buttstock of plastics.

The M16A1 was especially lightweight at 7.9 pounds (3.6 kg) with a loaded 30-round magazine.[77] This was significantly less than the M14 that it replaced at 10.7 pounds (4.9 kg) with a loaded 20-round magazine.[78]

Barrel

Early model M16 barrels had a rifling twist of 4 grooves, right hand twist, 1 turn in 14 inches (1:355.6 mm) bore – as it was the same rifling used by the .222 Remington sporting round. This was shown to make the light .223 Remington bullet yaw in flight at long ranges and it was soon replaced. Later models had an improved rifling with 6 grooves, right hand twist, 1 turn in 12 inches (1:304.8 mm) for increased accuracy and was optimized for use with the standard U.S. M193 cartridge.

Magazines

The M16’s magazine was meant to be a lightweight, disposable item.[112][113] As such, it is made of pressed/stamped aluminum and was not designed to be durable.[112] The M16 originally used a 20-round magazine which was later replaced by a bent 30-round design. As a result, the magazine follower tends to rock or tilt, causing malfunctions.[113] Many non-U.S. and commercial magazines have been developed to effectively mitigate these shortcomings (e.g., H&K’s all-stainless-steel magazine, Magpul’s polymer P-MAG, etc.).[112][113]

Production of 30-round magazine started late 1967 but did not fully replace the 20-round magazine till the mid 1970s.[113] Standard USGI aluminum 30-round M16 magazines weigh 0.24 lb (0.11 kg) empty and are 7.1 inches (18 cm) long.[114][115] The newer plastic magazines are about a half inch longer.[116] The newer steel magazines are about 0.5 inch longer and four ounces heavier.[117] The M16’s magazine has become the unofficial NATO STANAG magazine and is currently used by many Western Nations, in numerous weapon systems.[118][119]

M7 Bayonet

The M7 bayonet is based on earlier designs such as the M4, M5, & M6 bayonets, all of which are direct descendants of the M3 Fighting Knife and have spear-point blade with a half sharpened secondary edge.

The text in this Post by M38A1JEEP.us is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.